On a humid September morning, Grace Adeyemi watched the floodwaters swallow her shop in Yenagoa, Bayelsa. It wasn’t the first time. For the third consecutive year, the rains arrived with biblical fury, turning streets into rivers and sweeping away cars, goods, and livelihoods. Buildings collapsed, communities were displaced, and when the waters finally receded, Grace faced a heartbreaking choice: liquidate the livestock that served as her family’s insurance policy or watch her children go hungry.

She sold the goats.

Grace is among 29 million Nigerian adults, about 26% of the adult population, who have faced climate-related shocks firsthand. Her response mirrors what millions are doing now: making desperate financial choices that mortgage their futures to survive the present.

This isn’t a distant threat; it is an urgent financial crisis. From annual devastating floods in coastal areas to extreme heat and pest outbreaks across the North, climate change manifests in 29 million individual stories of survival. Yet, when climate investors gather to discuss Nigeria’s adaptation needs, Grace’s story rarely makes it to the boardroom. We track billions in climate finance flows, discussing seawalls, green bonds, and renewable grids. Still, we overlook the most vital data point: What do people do when the floodwaters arrive, and why does it matter?

This isn’t just a climate story; it’s fundamentally a financial inclusion story. And it’s becoming clear that we can’t effectively address one without understanding the systemic vulnerability revealed by the other.

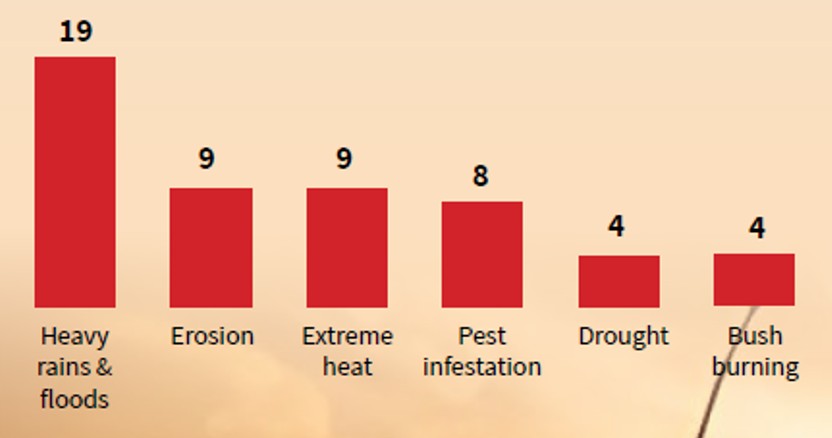

According to the A2F 2023 survey, approximately 29 million adults (26%) experienced a climate-related shock, such as heavy rains and floods, soil erosion, extreme heat, and pest infestations.

Have experienced climate-related events (% of adults)

Three out of every five people who experienced heavy rains, floods, erosion, drought, and pest infestations reported recurring damage from these climate change events. Similarly, half of those who faced extreme heat and bushfires reported repeated damage. This relatively high likelihood of recurrence increases the risk of escalating damage over time, thus raising the vulnerability of those affected. Repeated damage from climate change events can have severe humanitarian and economic impacts. Individuals and communities may face displacement, loss of livelihoods, damage to property and infrastructure, food insecurity, and adverse health effects. The cumulative impact of repeated climate-related disasters can worsen poverty and deepen socio-economic inequalities.

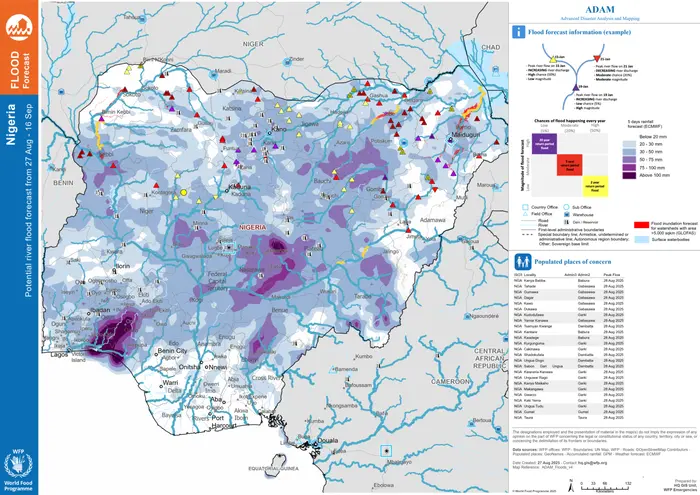

According to insights from the Relief Web below, there is widespread flood risk across major river systems, particularly in the central and southern regions, correlating with heavy 5-day rainfall accumulations (darker purple shades) and highlighting numerous locations, including major cities like Lagos, that are vulnerable to high-magnitude, low-frequency flood events.

THIS FLOOD FORECAST MAP FOR NIGERIA (AUGUST 2025)

Description and Map Guide:

This flood forecast map for Nigeria (August 2025) highlights areas at risk of riverine and coastal flooding. Shades of purple indicate rainfall accumulation over 5 days (darker shades = higher rainfall). Blue shaded polygons mark predicted flood inundation risk zones in major river watersheds. Various symbols show site monitoring locations, dams, and flood gauges. The table lists vulnerable localities experiencing peak river flows. Use the legend to understand flood magnitude probabilities and return period flood likelihoods (2, 3, and 20-year events).

Reference: World Food Programme (WFP) and ReliefWeb. Nigeria Potential River Flood Forecast, August 27 – September 16, 2025. Published August 2025. ReliefWeb.

The Erosion of Resilience: What 29 million Nigerians Are Actually Doing

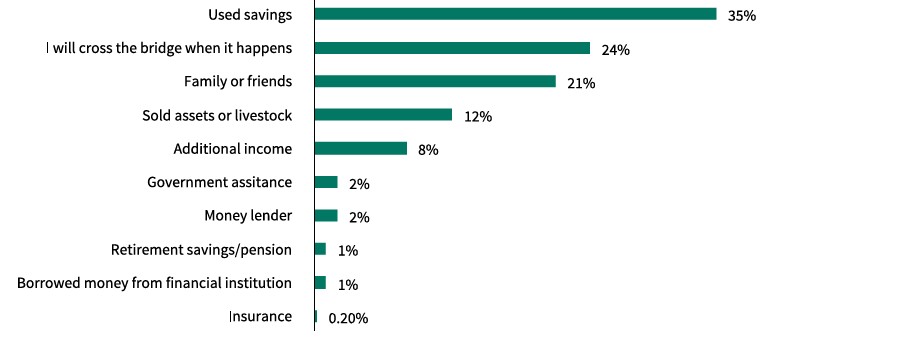

Examining how Nigerians deal with climate shocks shows a troubling pattern, not of inaction, but of actions that systematically weaken the resilience we’re trying to build. When faced with heavy rains, floods, soil erosion, extreme heat, or pest infestation, vulnerable populations are pushed into a destructive, invisible adaptation economy:

- 35% are depleting their savings to cope with shocks. These aren’t rainy day funds; they are becoming “flood and drought funds”, draining resources meant for education, healthcare, and economic advancement.

- 21% borrow from family and friends, turning social safety nets into financial obligations. When entire communities face simultaneous shocks, these informal networks collapse under collective stress.

- 12% are selling assets or livestock. As Grace knows, this is more than just liquidation; it’s the erosion of productive capacity. When farmers sell their breeding stock, they lose an asset and future income streams, food security, and the ability to withstand the next shock.

- Perhaps most alarming: 24% have no coping strategy, a signal not of optimism but of the complete absence of viable financial options.

These aren’t just isolated coping mechanisms, but warning signs of systemic financial weakness worsened by climate change. The recurring nature makes this disastrous: three out of five Nigerians who face floods, erosion, or drought report experiencing these events multiple times. This isn’t about bouncing back; it’s about being repeatedly knocked down, each time with fewer resources to cushion the fall and sacrificing more of the future to survive the present.

When Grace sells her livestock for the third time, what does she sell the fourth time?

The Barriers to Protection

Globally, insurance is recognised as a transformative force, a shield that protects against life’s uncertainties, from health crises to natural disasters. It allows individuals and communities to prevent, rebuild, and recover. However, this vital safety net is almost non-existent in Nigeria.

Despite the clear need, insurance penetration remains very low in Nigeria. As of 2023, only 3.1% (3.4 million) of adult Nigerians are insured. Millions stay unprotected, exposing them to financial risks worsened by climate change.

This lack of formal protection forces citizens into a destructive “Invisible Adaptation Economy.” When hit by floods or extreme heat, people resort to actions that systematically weaken the resilience they’re trying to build, such as depleting savings and selling productive assets like livestock.

Systemic Challenges in the Nigerian Context

At the macro level, the fundamental challenge is a geospatial and policy deficit. The absence of unified, high-resolution risk modelling, critical for accurately pricing complex, localised risks like flash floods in densely populated urban centres (e.g., Lagos) or micro-droughts in the North, renders comprehensive climate insurance virtually impossible for providers. Furthermore, the regulatory environment often lacks the incentives or mandates needed to scale products like national parametric flood pools or subsidised climate-risk coverage for the massive, predominantly informal, agricultural sector.

The meso level reveals a pervasive product and distribution mismatch. Traditional indemnity insurance models are ill-suited to Nigeria’s economy, which is dominated by smallholder agriculture and an informal workforce that cannot afford slow, complex claim processes. The market critically requires index-based insurance solutions that pay out quickly based on pre-defined climatic triggers (like measured rainfall or temperature deviations), but these remain underdeveloped. Crucially, distribution is hampered by poor infrastructure; while FinTech adoption is high, the insurance industry often struggles to leverage mobile platforms effectively, relying on physical agents instead of integrating with established mobile money networks to reach remote, vulnerable populations.

Finally, at the micro level, the core barrier is one of affordability and credibility. In an environment of persistent high inflation and currency devaluation, the premium for an appropriate climate policy often becomes prohibitively expensive relative to disposable income. This exacerbates the trust deficit, as many Nigerians perceive informal, community-based safety nets as more immediate and reliable than formal insurance policies whose claim processes are often perceived as slow, opaque, or subject to dispute. This failure to deliver relevant, affordable, and trustworthy systemic solutions directly escalates the climate vulnerability of the Nigerian populace.

The systemic deficits at the macro (risk-modelling and policy) and meso (product and distribution) levels do not exist in a vacuum; they translate directly into unacceptable user experience and profound market barriers on the ground. These structural weaknesses manifest acutely at the micro level, ultimately undermining the public’s confidence and ability to engage with formal risk transfer. This failure is evident in three critical, interconnected barriers that keep millions of vulnerable Nigerians perpetually outside the protection net.

- The Trust Deficit and Tardy Claims

The biggest obstacle is a profound lack of trust and confidence in the insurance industry, mainly because of the perception that claims are settled slowly and complicatedly. For many years, the industry has had a negative reputation based on experiences where claimants faced:

- Legitimate claims taking months to be paid, which is unacceptable for people who depend on their assets (like a business vehicle or farm produce) for daily income.

- Claims being denied on technicalities or needing too much evidence and paperwork.

- A recurring belief that insurance companies will find any reason to refuse payments.

This history means that even if a small farmer pays a premium, they often don’t believe the payout will arrive quickly enough to save their main assets. The ability to pay claims is the objective measure of a financially sound and reliable insurer, and progress slows down when they fail this test.

- Low Awareness and Product Literacy

The concept of insurance is still widely misunderstood in Nigeria, especially in the large informal and rural sectors.

- Knowledge about micro-insurance, which is created explicitly for low-income groups and micro-enterprises, remains very low at only 11% (12.2 million people) (A2F, 2023).

- A significant part of the uninsured population points to a lack of awareness about the products as the main obstacle, with many thinking they have “nothing to insure” or “don’t know the benefits.” Insurance is often viewed as an intangible luxury rather than a crucial financial security tool.

- Affordability and Product Suitability

- While 16% of the uninsured cite affordability as a barrier (A2F 2023), the issue extends beyond premium prices. For cash-strapped families like Grace’s, the cost-benefit analysis of a policy that may or may not pay out years later is often overshadowed by their immediate need for food.

- Most traditional insurance products are poorly suited for risks faced by subsistence farmers or small traders, especially when those risks involve large-scale, covariate weather events, such as widespread floods, that challenge conventional insurance models.

- Weather-indexed insurance (which provides payouts based on rainfall data rather than physical inspections) can be a solution. However, its adoption is limited by basis risk, the possibility that weather station data does not accurately reflect the farmer’s actual losses, leading to scepticism if the policy fails to pay during a loss.

By addressing this systemic failure, by restoring trust, aggressively boosting literacy, and designing products that truly meet the needs of the climate-vulnerable, Nigeria can unlock the potential of insurance as the primary tool for building sustainable financial resilience.

Reframing Adaptation: A Mandate for Financial Resilience

To provide reliable, non-destructive coping mechanisms, we must integrate financial inclusion and climate adaptation by prioritising risk transfer and awareness. The solution lies in building an ecosystem for climate-resilient financial services:

- Market Incentivisation and Risk Capital (DFI/Government Mandate)

Given the scale and covariance of Nigerian climate risks, the private insurance market will not engage effectively without public support to absorb catastrophic risk and offset initial technical costs. Government, Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), and donors must actively incentivise insurers.

- Establish a National Disaster Risk Pool (NDRP):

The government, possibly leveraging existing climate funds (e.g., the Nigeria Green Bond Programme’s adaptation component or a new dedicated facility), must capitalise a sovereign or regional reinsurance mechanism. This pool would provide a layer of subsidised reinsurance capacity for climate-risk products (especially flood and drought) written for vulnerable populations, thereby reducing the extreme capital exposure for local insurers.

- Climate Fund Access for Risk Transfer:

Nigerian climate funds (including any Green Bond proceeds allocated to adaptation) must explicitly clarify and establish a window for local insurers and reinsurers to access funds for two purposes:

- Data & Tech Investment: To co-fund the development of high-resolution geospatial risk models and digital infrastructure necessary to price complex risks and improve the accuracy of weather-indexed insurance, directly mitigating the basis risk problem.

- Premium Subsidy Backstopping: To serve as a public partner in a cost-sharing model for the “Enhance Affordability” plank below, thereby providing certainty to insurers on subsidy payments.

- Tax and Regulatory Incentives:

The National Insurance Commission (NAICOM) should introduce capital relief (lower solvency requirements) for insurers underwriting accredited micro-insurance and parametric climate products, and grant tax breaks on premiums earned from these segments.

- Boost Financial Literacy and Trust:

- Concerted efforts are needed to enhance financial literacy and build trust. This entails implementing targeted education campaigns, leveraging digital technologies, and fostering partnerships between insurance companies, government agencies, and civil society.

- Educational campaigns and community outreach can dispel misconceptions and build confidence in insurance providers, ensuring more Nigerians have the financial tools they need to weather uncertainties.

By holistically addressing the penetration and awareness barriers, Nigeria can unlock the potential of insurance as an essential tool for promoting financial resilience. The answer to Grace’s predicament is not just more humanitarian aid after the flood, but a reliable, formal risk management tool before the rain starts.